Wardley Map — Cognitive Hierarchy

What I’ve found helpful in maintaining my ardor as I get to grips with complex topics has been a Wardley Map of a “Cognitive Hierarchy,” a hierarchy I came across a while ago1. Even though it’s explained in the context of war, I’ve found it useful when also applied to my studies. Perhaps it might do the same to yours.

Many subjects that I’d like to get into require time from me to understand, even if I limit myself to Hamerton’s definition of “soundness,”2 which is below:

The best time-savers are the love of soundness in all we learn or do, and a cheerful acceptance of inevitable limitations. There is a certain point of proficiency at which an acquisition begins to be of use, and unless we have the time and resolution necessary to reach that point, our labor is as completely thrown away as that of mechanic who began to make an engine but never finished it. . . .

On labour versus the accomplishment:

Now the time spent on these unsound accomplishments has been in great measure wasted, not quite absolutely wasted, since the mere labor of trying to learn has been a discipline for the mind, but wasted so far as the accomplishments themselves are concerned. . . .

Defining “soundness” and its examples

I should define each kind of knowledge as an organic whole and soundness as the complete possession of all the essential parts. For example, soundness in violin-playing consists in being able to play the notes in all the positions, in tune, and with a pure intonation, whatever may be the degree of rapidity indicated by the musical composer. . . .

A man may be a sound botanist without knowing a very great number of plants, and the elements of sound botanical knowledge may be printed in a portable volume. . . .

Suppose, for example, that the student said to himself “I desire to know the flora of the valley I live in,” and then set to work systematically to make a herbarium illustrating that flora, it is probable that his labor would be more thorough, his temper more watchful and hopeful, than if he set himself to the boundless task of the illimitable flora of the world. . . .

Lastly, it is a deplorable waste of time to leave fortresses untaken in our rear. Whatever has to be mastered ought to be mastered so thoroughly that we shall not have to come back to it when we ought to be carrying the war far into the enemy’s country. But to study on this sound principle, we require not to be hurried. And this is why, to a sincere student, all external pressure, whether of examiners, or poverty, or business engagements, which causes him to leave work behind him which was not done as it ought to have been done, is so grievously, so intolerably vexatious.

Since some of these topics are not necessarily related to my job, it means spending some of my spare time on them. Suppose that to acquire soundness in topic ‘X’ requires 40 hours; if I have 2 hours per day that are free from interruptions, I would need 20 days (almost 3 weeks) for such an acquisition. This also assumes that I’m pursuing only that one topic. I leave it you to imagine what happens when tackling other topics at the same time, varying them to break the monotony. After the initial enthusiasm wanes, is endurance called for, so as to maintain the consistency of working on it daily; or like John Foster once called it, “this indefatigable patience of exertion.”[5]

For that, having an assurance that it’s worth it for me is encouraging. This is where having maps that I can frequently review maintains my ardour. They also help me decide whether to pursue a particular subject, and, most importantly, to what extent. After all, “the time given to the study of one thing is withdrawn from the study of another, and the hours of the day are limited alike for all of us.”

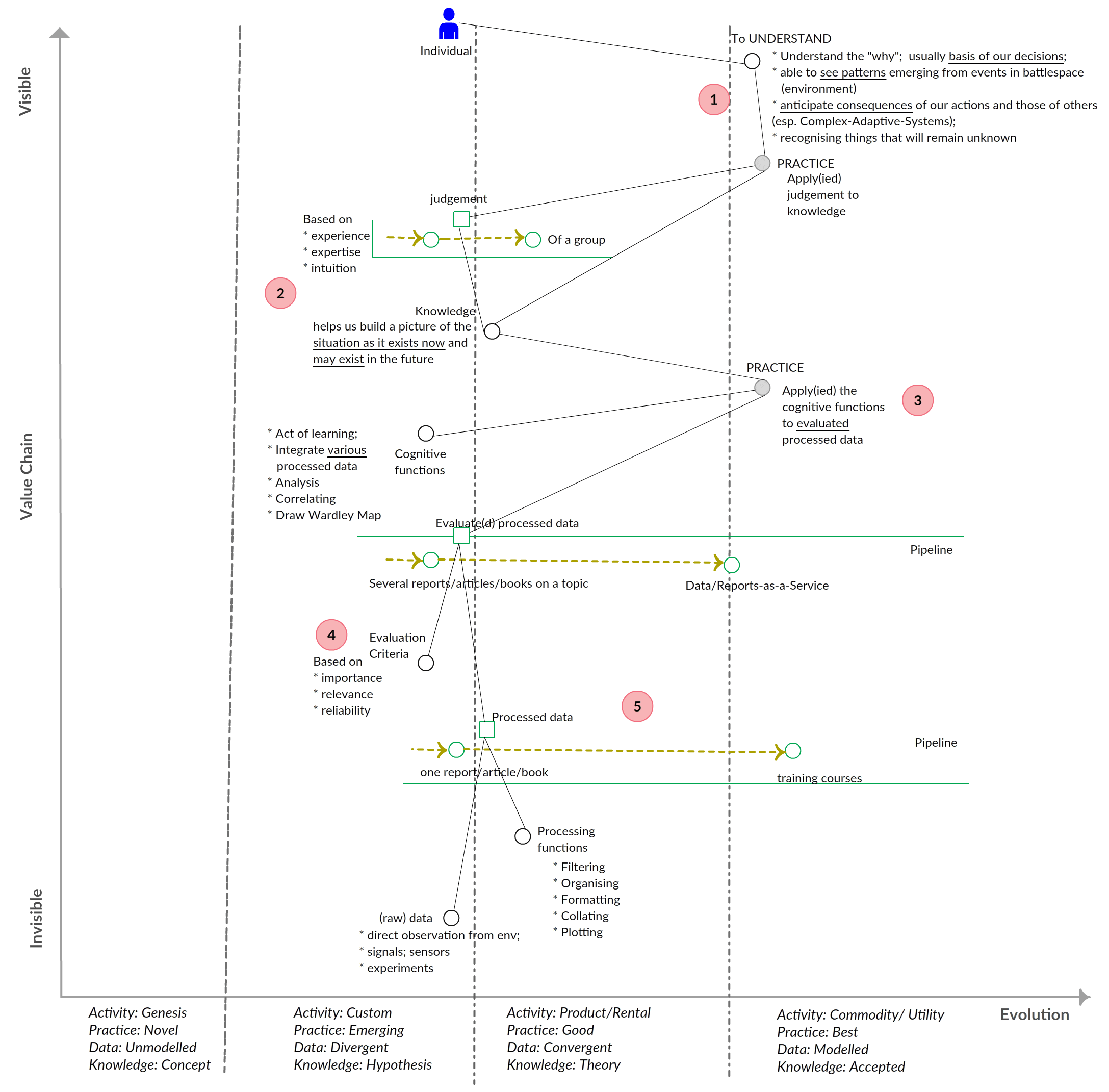

What would the map of an individual (in this case, me) look like ? Some aspects are applicable to groups/teams, but I wanted to keep the scope as narrow as possible. Because it’s for an individual, most components are in the “Custom” phase, e.g., the person has to perform analysis; it’s not something that can be delegated/outsourced.

Map of the Cognitive Hierarchy

Map of the Cognitive Hierarchy

1. The first user need is to understand a topic, especially, as it relates to either help in arriving at a decision (perhaps “to decide” should be the top-level user need) or to see patterns or to anticipate the consequences of others’ (or my) actions. To decide, to see patterns, to anticipate consequences — all these are applicable in many contexts — at work, at home, and in the community. If a topic does not help me with these, I often lay it aside. I’m excluding those that are for amusement — but even with these, it’s almost an impossibility for them not touch those three points.

2. Having selected, and committed to, such a topic, there’s the need to apply “judgement,” which is not only knowing that something is but why it is so. Based on one’s experience, expertise, and intuition, one also develops principles (or the inner workings) that can explain what’s going on. Yet without such experience or intuition, so do they need be built up. One cannot apply the judgement he/she does not posses. Therefore, there’s the need for the next component: if I practise applying these cognitive functions to the processed data, I’ll be able to construct a mental model/picture of the current situation/environment and be able to make decisions that anticipate what others might do, owing to the principles/laws/patterns that have caused the situation in the first place.

3. Once we have various processed data that have been evaluated (either by oneself or by others), there’s the need to apply those “cognitive functions,” to harmonise them. If applied to studies, “comparing text with text,” as Sertillanges encourages us, “making the different sources of information complete, illustrating one with the other, and draw[ing] up your own article.” As he concludes, he reassures us, “It is an excellent gymnastic, which will give your mind flexibility, vigor, precision, breadth, hatred of sophistry and of inexactitude, and at the same time insure you a progressively increasing store of notions that will be clear, deep, consecutive, always linked up with their first principles and forming by their interadaptation a sound synthesis.”3 Such links to first principles lend themselves to drawing Wardley Maps 🙂

That’s where the difficulty manifests itself — where does one begin, and end, with the many resources (print, video, audio, etc) on a topic ? Which of them to gather? How many of them can one get through, knowing that each differs in style, breadth, depth ? How to bring them to terms, to find and state their propositions, their arguments, and their solutions, if any ? Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren4 help us here. This calls, once more, for that “indefatigable patience of exertion.”

There’s also that feeling that John Foster5 so aptly describes:

Is it, then, in the first place, that a man can instantly place himself among the subjects of knowledge, and begin to take possession, without the cost of any tedious forms of introduction? No; he must consume in all a number of years in the acquisition of mere signs; in the irksome study of terms, languages, and dry elementary arrangements. Is it, that having thus fairly arrived within the boundary of the ample and diversified scene, he is certain to take a direction toward the richest part of it, and with the best guides? He may happen to be led by some casual circumstance, or to be attracted by some delusive appearance, to a department where his mind will exhaust its strength in endless toils, to reap nothing but a few vain and pernicious dogmas. He may be as if Adam, when “the world was all before him where to choose,” had been deserted by “Providence his guide,” and beguiled to wonder into what is now Siberia.

Or if a man in quest of knowledge should have directed his view to a more valuable class of subjects, he may waste a great deal of labour and time, and be often tempted to renounce his purpose in disgust, through an unfortunate selection of instructors and guides.

Hence the reason to be severe with those who profess to instruct; and the necessity of critically reviewing each work, such that the criticism serves as a signpost to encourage other travellers to the helpful, or as a warning sign advising them not to approach. This is where Simon Wardley’s “Tomb of Tomes” would come in handy 🙂

4. For that sifting to occur, these have to evaluated based on some criteria — e.g., their importance, relevance, and reliability. But then, the question becomes “important” to whom ? What’s important to me may not be important to you. Moreover, even if I limit this check to myself, what’s important to me now may not be what’s important to me a few months/years’ time. Because I have to apply these criteria frequently, I’ve left this activity in the “Custom” phase.

5. At this point, only one book is under consideration. For it to have been produced required someone to apply the processing functions to raw data.

What limits do I see in such a map have ? Firstly, this map is for a cognitive hierarchy. It’s generic. It’s not specific to any subject nor to any industry/company/team. In order to apply it to something specific, e.g., to learn about AWS or Azure or Bash shell scripting, you’d need to map your industry/company/team to see where such knowledge sits in the phases of evolution. This, in turn, determines how much to invest and what the expected return is. Next is to overlay one map on the other. If the lower components of the chain are seen as commodities in their respective markets/industries, then you can focus on steps 1 and 2 only.

Secondly, this map doesn’t show any higher-order activities that result from, and build on, more commodotised components.

How does such map help me? Firstly, because of the constraint of time, I’d prefer to only perform activities in step 1 and 2. But, lacking those, I have no choice but to continue descending the value chain. For topics that can be traced back to a few excellent books, I skip (or rather, defer) tackling the many books — the second pipeline — and focus on the books that expressed the initial idea. Sometimes, I find it necessary to descend lower, and apply the processing functions to the author’s raw data, if appropriate/applicable. This is one reason I read, with keen interest, the bibliography or references sections of books and article. And why, I, too, include them in what I write.

Secondly, I’ve noticed that the further down the chain I go, the more time I’ll need to ascend up again. I may be on step 5 for months (according to the 2hr per day guideline), making some progress, but still at the bottom of the chain. Looking at the user need repeatedly refreshes, renews my vision of the goal and sustains me in my pursuit.

This, I’ve found to be a pleasant side-effect.

Footnotes

pp. 20–23 of “Naval Doctrine Publication (NDP) 6” ↩︎

pp. 93-96 of “The Intellectual Life” by Philip Gilbert Hamerton. (Affiliate link) ↩︎

p. 113 of “The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods” by A.G. Sertillanges, translated from the french by Mary Ryan, 1987 edition, reprinted in 1998. (Affiliate link) ↩︎

pp. 114–136 of “How to read a Book” by Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren ↩︎

p. 118 of “The Improvement of Time” by John Foster, edited by J. E. Ryland (1863) — Google Book ↩︎